We asked astrophysicist and all-round excellent human Jen Gupta to write about this month’s solar eclipse for our website. Read on to find out what an eclipse is, why they happen and how you can enjoy it safely on Friday 20th.

In the morning on Friday 20th March 2015 a partial solar eclipse will be visible from the UK. In Manchester the eclipse will start at 08:26 and finish at 10:41 with the maximum obscuration at 09:32. At this point, 90% of the Sun will be covered up and will look something like the image found here.

The timings of the eclipse and how much of the Sun gets covered up will be slightly different depending on where you are in the country. Where I work in Portsmouth, the maximum will happen four minutes earlier and only 85% of the Sun will be covered up. Go north to Edinburgh and the maximum obscuration will be 93% at 09:35. Of course realistically it won’t really look different wherever you are in the UK. To see the total solar eclipse, with the Sun completely obscured by the Moon, you’ll need to go way north, to the Faroe Islands or Svalbard.

The timings of the eclipse and how much of the Sun gets covered up will be slightly different depending on where you are in the country. Where I work in Portsmouth, the maximum will happen four minutes earlier and only 85% of the Sun will be covered up. Go north to Edinburgh and the maximum obscuration will be 93% at 09:35. Of course realistically it won’t really look different wherever you are in the UK. To see the total solar eclipse, with the Sun completely obscured by the Moon, you’ll need to go way north, to the Faroe Islands or Svalbard.

Click here to see information about the eclipse in different locations

In this post we’re going to look at eclipses in more detail, including what an eclipse is, why they’re interesting, and, perhaps most importantly, how you can safely view March’s partial eclipse.

What is an eclipse?

A solar eclipse happens when the Moon passes directly in front of the Sun as we see it from Earth, blocking out the light coming from the Sun. From this simple explanation you might be wondering why we don’t get a solar eclipse every 28 days, as the Moon orbits around the Earth. Well it’s all to do with how the Earth, Moon and Sun line up (or don’t). The orbit of the Moon around the Earth is tilted at a small angle compared to the orbit of the Earth around the Sun. This means that if you draw a line from the Earth to the Sun at ‘New Moon’ (when the Moon is in between the Earth and Sun), most of the time the Moon will be above or below this line. But every now and again it lines up perfectly, and that’s when we get a solar eclipse.

It just so happens that the apparent sizes of the Moon and the Sun from Earth (in other words, how big they look to us) are pretty much the same, so during a total solar eclipse the Moon completely blocks out all of the light from the Sun. To witness this you need to be in the ‘umbra’ in the diagram below. Surrounding the umbra is the ‘penumbra’ where only part of the Sun will be blocked out, and this is where you need to be for a partial eclipse, like we will be in the UK on 20th March.

You may have also heard of lunar eclipses. These happen at ‘Full Moon’ when the Earth is directly between the Sun and the Moon, and the Earth casts a shadow on the Moon. You can find out more about lunar eclipses here.

How to view the eclipse

The most important thing to take away from this section is that you should never ever look directly at the Sun, not with your eyes, binoculars or a telescope! This still applies during an eclipse, especially when it’s only partial (in theory it would be safe to look during totality, when the Sun is completely covered by the Moon, but we won’t see this from the UK in March). More detailed safety information about viewing solar eclipses can be found on the NASA website.

There are two main ways that you can safely view the partial eclipse in March. One way is to look at it through something which blocks out most of the Sun’s light. Sunglasses definitely won’t do here! What you need are special eclipse glasses or viewers, or a special solar telescope. Both use a material to block out at least 99.999% of the Sun’s light, reducing the intensity to a level that is safe for your eyes. You can buy eclipse glasses and viewers from various places, such as here and here. Or get a free pair with this month’s Sky at Night magazine! Make sure that you buy eclipse viewers from a trusted company and check them for damage before each use. Solar telescopes are pretty expensive but you might find an event near you where one will be available for you to look through.

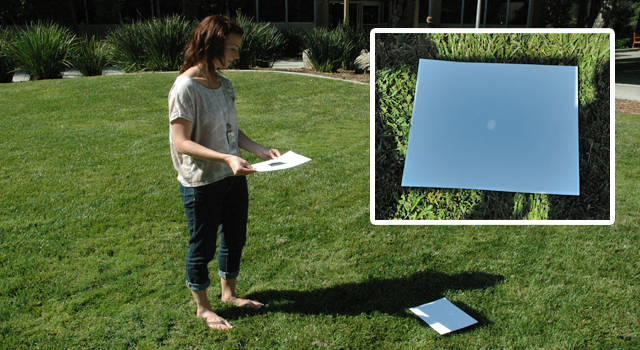

The other way to view the partial eclipse is by projecting it onto a surface, as shown below. There are various ways that you can do this, and you can find instructions on how to make an eclipse projector here, here and here. You can even use unusual objects to project an image of the Sun – in Portsmouth we’re going to try using an aluminium plate from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Why are eclipses interesting?

As well as being fascinating events for us to watch, solar eclipses also provide a unique opportunity for scientists to carry out research.

Total solar eclipses allow astronomers to observe and take measurements of the Sun’s corona, or atmosphere. One of the big unanswered questions in solar physics is why the corona gets so hot – the temperature of the corona is around one million degrees Celsius, while the surface temperature of the Sun is ‘only’ about 6000 degrees C, and we don’t know why. To see the Sun’s corona, astronomers normally have to use a special instrument on their telescope called a coronagraph, which blocks out the light coming from the disk of the Sun. During a total solar eclipse though, the Moon acts like a natural coronagraph and actually allows astronomers to see parts of the corona that are closer to the Sun’s surface. You can find out a bit more about this on the sun|trek website.

Nearly 100 years ago, a total solar eclipse also helped physicists to test Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity for the first time. The theory of general relativity says that light will be bent, or deflected, by anything with mass. In order to observe this effect though you need something that’s really massive, like a star, to bend the light enough to be measured. Physicists realised that you could use the Sun as this massive object and observe the bending of light from distant stars as the Sun passed in front of them. Normally the Sun’s light means that you can’t see the stars behind it but during a total eclipse it will be dark enough to observe them. In 1919 Arthur Eddington led an expedition to observe the Hyades cluster of stars during a total solar eclipse, and compared their positions to observations taken months earlier. The measured positions matched up with the predictions made by Einstein’s theory of relativity, and helped turn Einstein into the household name that he is today.

It’s not just astronomers who do experiments during solar eclipses. Scientists from the University of Reading’s meteorology department are running a citizen science project to look at how the weather changes when the Sun’s light and heat is blocked out during March’s eclipse. Find out how you can get involved on the National Eclipse Weather Experiment website.

What next?

Hopefully this will have inspired you to go out and watch the partial eclipse on the 20th March. You can buy eclipse viewers or make your own solar projector as described above. There are events taking place around the country to bring people together to observe the eclipse: find your local one here. The BBC will also broadcasting a special episode of Stargazing Live, which will also be shown on some of the Big Screens (including Portsmouth).

If you fancy witnessing a total solar eclipse for yourself then you can find details of future eclipses on NASA’s website. I’m starting to plan an eclipse trip to the US in 2017 already!

We’ll be heading along to the eclipse event at MOSI on Saturday 21st March – click here for more details.